The Tax Cuts and Job Act of 2017 (TCJA) ushered in several significant changes for the individual taxpayer. Among the changes going forward is a cap on the deduction available for each taxpayer’s combined property taxes, as well as state and local income taxes. While a larger standard deduction and more favorable tax brackets will offset the potential tax increase for most clients, this should cause many taxpayers to pay more attention to the cumbersome property tax that all residents of the Buckeye State must pay. In this article, we dig into the history of property taxes in Ohio and cover a few components of the tax to which you may not be familiar.

A Little History:

The real property tax is Ohio’s oldest tax, originating in 1825. It is 110 years older than the retail sales tax (although sales taxes on cigarettes and gasoline were in existence prior to 1935), and nearly 150 years older than our notorious income tax, which was born in 1971. The real property tax has always been an ad valorem tax, meaning it is based on the assessed value of the property being taxed.

The original purpose was to provide funding support for public schools, and it was a huge departure from the state’s general rule on avoiding all property or income taxes. At that time, the state government imposed a half-mil property tax, which is equivalent to $0.50 per $1,000 of taxable property value.

Applying the Taxes:

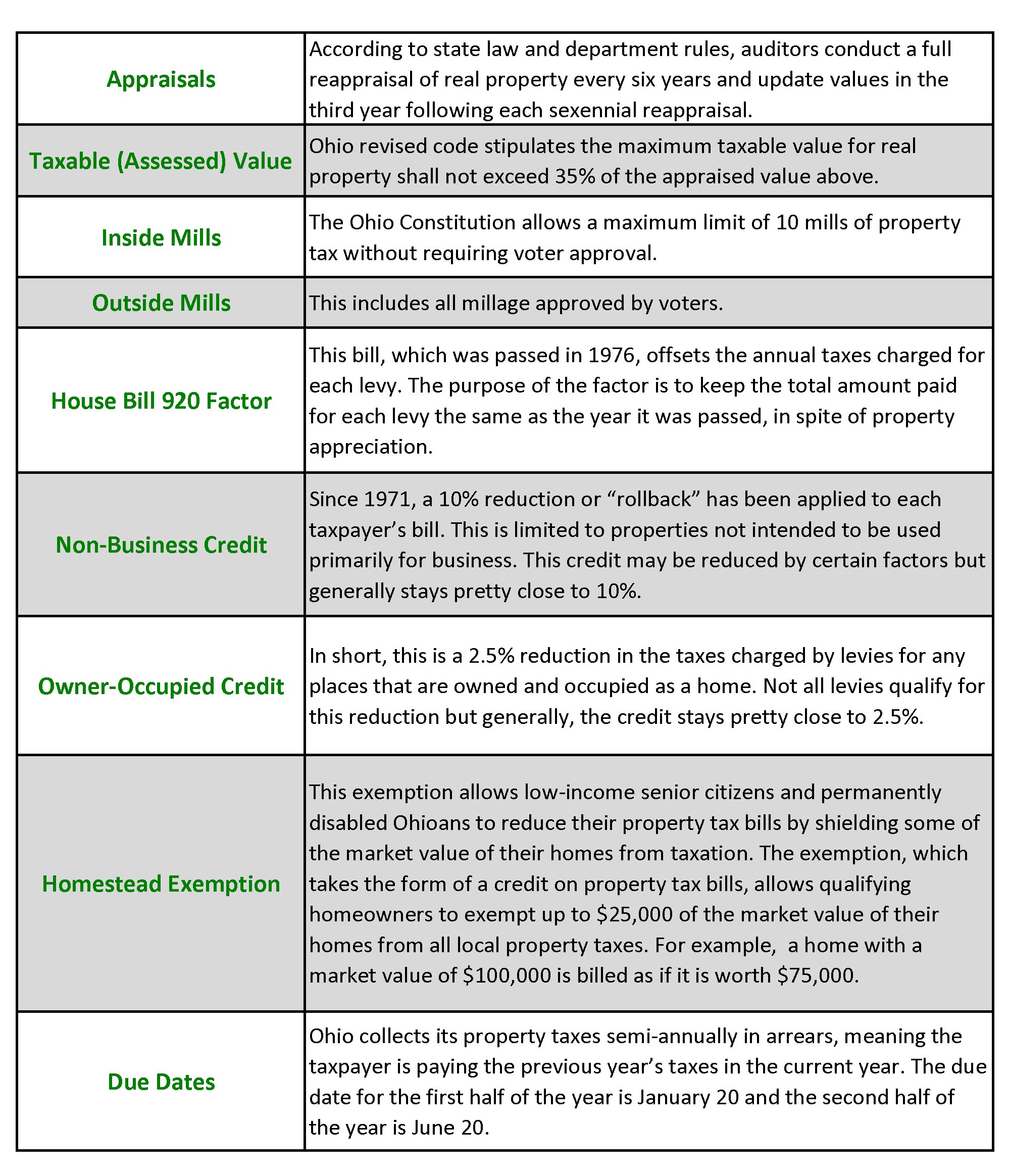

Although determining your property taxes may seem as simple as multiplying the value of your property by the millage rate, it is far from being that easy. Before I explain this in more detail, here are some things to know:

Here is an example of the process for a hypothetical $500,000 home located in Upper Arlington, Ohio. First, the county auditor completes an appraisal of all properties in the area and calculates the tax rates based on levies approved by voters. Keep in mind, the total millage rate is reduced accordingly to satisfy HB 920 mentioned above.

In this example, the total tax rate in Upper Arlington is 141.90 mills. The HB 920 factor for reduction is 0.458, resulting in an effective millage rate of 76.90. The appraised value is lowered to 35% of the appraised value, resulting in a taxable value of $175,000. The next step is to apply the aforementioned millage rate of 76.90 to the number of mills for the property

→ $175,000 divided by $1,000 = $175 → 175 x 76.90 = $13,457.

This annual tax amount is then reduced by the 10% non-business credit and 2.5% owner-occupied credit to arrive at the taxpayer’s final tax bill for the year of $11,775.

Other Points of Interest:

- CAUV – For property tax purposes, farmland devoted exclusively to commercial agriculture may be valued according to its current use rather than at its “highest and best” potential use. This provision of Ohio law is known as the Current Agricultural Use Value (CAUV) program. By permitting values to be set well below true market values, the CAUV normally results in a substantially lower tax bill for working farmers. To qualify for the CAUV, land must meet one of the following requirements during the three years preceding an application:

- Ten or more acres must be devoted exclusively to commercial agricultural use

- Or, if under ten acres of commercial agricultural use, the farm must produce an average yearly gross income of at least $2,500

- Oil and Gas Real Property Taxation – Ohio taxes oil and gas reserves as real property. All property taxes are charged and collected at the county level and support schools, townships, municipalities, counties, libraries and special service districts. Once production of the oil or gas reserve begins, its taxable value is determined by the application of an appraisal formula.

- Real Property Conveyance Fee – The real property conveyance fee is paid by persons who make sales of real estate or used manufactured homes and consists of two parts:

- A statewide mandatory tax of one mill ($1 per $1,000 dollars of the value of property sold or transferred)

- In addition, counties may also impose a permissive real property transfer tax of up to three additional mills.

A Little Controversy:

Since the real property tax debut in 1825, Ohioans have debated the merits of this funding model for public education. Ironically, in 1935 the state legislature implemented the Ohio Retail Sales Tax Law to help prevent the financial collapse of the public school system as the Great Depression rendered many Ohioans unable to pay their property taxes, thus eliminating much of the education funding. In 1991, 500 school districts filed suit against the state for failing to provide adequate funding to educate students. In 1996, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled the current method of funding violated the Ohio Constitution.

Furthermore, from 2000 – 2002, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled again that the school-funding process in Ohio remained unconstitutional, and ordered the state government to “enact a constitutional school-funding system”; however, the court eventually determined that the Ohio government had made a good-faith effort to change public school funding, and the justices overturned their earlier rulings.

How Do We Rank:

According to WalletHub.com, when ranked by the effective tax rate, the state of Ohio ranks 12th highest in the nation for property taxes. While this may seem like a raw deal for Ohioans, this rate must be put into context. For example, consider the median home value of $131,900, which ranks Ohio as 9th lowest in the country. By applying the effective tax rate to our median home value we become the 20th highest in the nation. While this is still not great, we must remember the other means through which we fund our state government, income and sale tax. It is beyond the scope of this article to rank us according to those metrics, but hopefully, you now have a better understanding of the property taxes we pay and where they originated.